What must we do? The Good Samaritan as a window into understanding Christian vocation

Many have heard the

term "Good Samaritan". It is often used in our contemporary culture

to describe a helpful person, someone who goes out of her own way to meet another's

dire need.

The story of the

"Good Samaritan" only occurs in the Gospel of Luke. And it's actually

(more accurately) a story about an encounter between Jesus and a religious

scholar (Luke 10.25-37). The good Samaritan makes an appearance in this

encounter as the means by which Jesus responds to the religious scholar’s

question about neighbor love.

In order to hear this

story afresh, this encounter between Jesus and the legal scholar, it is

helpful to know that it falls within a larger literary context (Luke

9.52-19.48) sometimes referred to as the "journey section". In this

larger portion of the Gospel, Luke highlights Jesus' approach to Jerusalem,

where his confrontation with religious and political leaders will come to a

climax, where he will be considered an outsider buy the religious establishment

who is stripped, beaten, and left for dead. Two themes emerge throughout this

"journey section", themes that are helpful for deepening our

understanding of Christian vocation: (1) through Jesus, God is fulfilling and

embodying His promise to redeem Israel, and through Israel the entire world,

from its rebellion and slavery, from its oppression and assault by the evil one;

and (2) this redemption comes, in part, through the (re)formation of a

people of God who not only know and hear God's word, but who will also obey it,

put it into practice. In this section of the Gospel, Luke has included and

arranged these particular happenings with Jesus so as to underscore who God is,

and that we have been invited to join in God's mission of redeeming this world

by doing what He calls us to in His word. With this as the backdrop, the stage

is set for a challenging reflection on what it means to respond to God's

call.

What must we do to

inherit eternal life? It is not necessarily a question we would ask Jesus

today. We might ask him something like, what must we believe, or

what must we affirm? What prayer must we pray? Or perhaps,

what worldview must we hold?

Luke tells us about a

religious scholar, a teacher of the Law, one who has dedicated his life to correctly

understanding what God has revealed to Israel and how to work that revelation

out where the rubber meets the road in daily life. This religious scholar,

shaped by the thought world of the Torah asks Jesus, "What must I do to

inherit eternal life." From his reading, thinking, and religious

formation, he knows that faith without works is dead; that affirmation without

action is an aberration. He knows that to hear the word of the Lord does not

merely mean to know it but also to do it. It is particular practices,

those prescribed by the one true God in the Holy Scriptures, that mark out

those who belong to the life of the world to come. This legal expert is not so sure

that Jesus has the correct interpretation of those practices.

We gather this from

the way that Luke describes the origin of their encounter: the religious

scholar, this 'lawyer' or 'scribe' as some English translations render it,

"stood up to entrap Jesus" (Luke 10.25). We don't know exactly why

the religious scholar is suspicious, but this question that he asks Jesus has

bite to it. "Teacher," (does he say this scoffingly?) he says,

"what must I do to inherit eternal life?" Throughout the narrative of

Luke's Gospel, religious scholars are found monitoring Jesus' teachings to

discern whether they concord with the Bible (or at least their interpretation

of it). The narrative world of Luke also colors our expectations of religious

scholars because they are included in the list of people who rejected Jesus and

worked to have him crucified.

Jesus responds with

two of his own questions: What is written in the Law? And, How

do you read it?

The religious scholar

is in his sweet spot, he gets to talk about his knowledge of the Bible! He

responds with a concise and perceptive summary of all that the Law teaches:

"You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your

soul and with all your strength and with all your mind (Deut 6.5) and your

neighbor as yourself (Lev 19.18)." Mark (12.30) tells us that this is

precisely what Jesus answered when a scribe asked Jesus which commandment was

the most important of all. Loving God with all our being and loving our

neighbor, this is our duty to God, our vocation or calling. This is God's

vision for us; it’s how life is made to work.

Unsurprisingly then,

Jesus retorts that the religious scholar has answered correctly. "Do

this," Jesus exhorts, "and you will live (Luke 10.28)."

But Luke tells us

that the religious scholar is not done yet. He has one more qualifying question

for Jesus. In fact, Luke tells us that this man who has dedicated his life to

the knowing and teaching God's revelation to Israel wanted to "justify

himself", asking Jesus "And who is my neighbor?"

It is perhaps illuminating

that the scholar did not feel that he needed clarification on what it means to

love God with his whole being. Maybe he felt as though he had that part down.

What he did want to know is who qualified as a neighbor. Luke doesn't tell us

why this question was important to the religious scholar, but instead only

gives us the motive for asking--"he wanted to justify himself."

Perhaps he wanted to know the boundaries or limits of neighbor love; perhaps he

was asking so that he would know who he did not have to show love to.

Jesus gave him

clarification by telling him a story about an anonymous, label-less man who was

going down from Jerusalem to Jericho. On his journey, this man fell among thugs

who stripped him, beat him, and left him for dead. Luckily (and it seems that this

is said with a tinge of sarcasm) for this man who has been left for dead, a

priest was also going down that road. This priest who knew God's word, served

him in the temple, and taught Israel about what it meant to love God saw the

man left naked and half dead...and passed by on the other side.

Likewise, a Levite, a

man who came from the tribe of Israel that was in charge of helping mediate

God's life to God's people for the sake of the world, came to the place

where the naked, beaten, anonymous man languished. He also saw this

man...and passed by on the other side. Apparently for these two men, an

anonymous man, a man whom they did not know, a man with whom they held no bonds

of kinship or friendship, a man who had nothing to mark him as a neighbor (at

least not in the narrative), whom they happened to stumble upon in the course

of their daily affairs, was not a neighbor that they were obligated to love.

For them, he did not possess the status of neighbor.

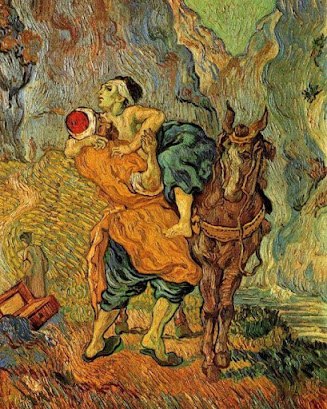

The story climaxes

with the entrance of a Samaritan. Someone whom the Jews regarded as an outcast,

a non-neighbor, a heretic, and a worshipper of a false god. The narrative of

Luke's Gospel thus far has prepared us to be suspicious of any encounters with

Samaritans (Luke 9.53). This Samaritan came upon the naked, beaten, half-dead

man, and when he saw the destitute man, he had compassion on

him. Rather than pass by on the other side, he went to him (Luke

10.35), and bound up his wounds with oil and wine. What is more, he put the

battered man on his animal, brought him to an inn and took care of him to make

sure he was healing properly. The next day he gave the innkeeper what amounted

to something like two one hundred-dollar bills, probably enough to cover three

weeks of lodging, and asked him to take care of the man until he returned. The

Samaritan showed extravagant generosity, risking much more than was required of

him in an effort to care for the man who fell among thugs, putting his own life

in harm's way by taking him to an inn (not a reputable place in the first

century), and by sacrificing his resources to assure that the man would

recover.

Jesus then asked the

religious scholar a question: "Which of these three, do you suppose,

became a neighbor to the man who was beat up by the thugs (Luke 10.36). The

religious scholar, caught in his own trap, responded, "the one who did mercy

to him" (Luke 10.37).

It is important to

underscore that with this response, the religious scholar was evoking a phrase

that encapsulated God's call for the people of Israel--to do, practice,

demonstrate mercy. For in the Torah, mercy is not just a feeling of pity; it is

rather an action that we engage in.

"You go,

and do likewise," Jesus concluded.

The story ends as a

kind of microphone drop. The religious scholar who sought to entrap Jesus has,

with his own words, answered his own question: to love our neighbors we must

become neighbors to them. He has heard this word afresh; but will he do it? We

don't know, but in ending the story in this way, the same question confronts

us, especially as we read this story in its larger literary context. We have

heard the word; we know what we must do. Will we do it?

The religious scholar

wanted to define what a neighbor was, wanted to know what the limits of

neighborly love was. Jesus responded by explaining that the ethos of the

command to love your neighbor as yourself was not to focus on who may or may

not be one's neighbor, but rather it was to become, to see yourself as a

neighbor to others. To say it another way, one does not have a neighbor,

instead one becomes a neighbor to those in need. With this story of the Good

Samaritan, Jesus redefined "neighbor" from being an object to being a

subject. The religious scholar wanted an abstract discussion about what a neighbor

is and isn’t; Jesus turned it into an exhortation to personally engage in acts

of mercy to anyone who is in need. For Jesus, the point of loving one's

neighbor is not to figure out who can be excluded from that love, but rather

loving God with all your being by becoming neighborly to all, even those

outside of your kinship and friendship bonds.

What is more, we

exercise this neighbor love "on the way", in the course of our daily

affairs. To love God and neighbor is to practice faithful presence: to be

present enough to see those who are in need of mercy and to

move towards them with our resources in order to bring healing.

As we think about

Christian vocation, this encounter between Jesus and the religious scholar

serves as a window through which we see what it looks like to respond to God's

call. We are called to go on our way in the love of God, and as we go, we are

called to faithfully respond to the needs that we see before us. Rather than

pass on by, we are called to become neighborly to those that we see have been

left for dead.

With this encounter,

we are also reminded that Christian vocation is not expressed merely in terms

of knowing the right things about who God is and how we are called to love him.

Christian vocation is more than knowing a worldview, more than knowing

propositions that God has revealed. to us Rather, a faithful expression of

Christian vocation is found in the doing of mercy.

As we learn from

other teachings and stories from Jesus (e.g. Luke 19.1-10; Matt 18.21-35; John

15.1-17), when we do mercy we demonstrate that we have in fact inherited

eternal life, because we exhibit that we share in God's life of mercy.

So, as we seek to

understand our Christian vocation, let's hold this story of Jesus close to us.

Our mission is to share in God's life of love for the world. This mission is

worked out in everyday encounters with others, where we are called to see and move

toward darkness, death, corruption, violence, and use our resources to

bring healing.

Comments

Post a Comment